Businesses, policymakers and educators keep a close eye on population trends. Schools need to prepare for future students. Businesses want to recruit from a deep and skilled talent pool. Lawmakers and state officials seek information about this crucial group so that their policy decisions will benefit the economy and enhance the state’s way of life. Virginia added 630,000 people since 2010, a 7.9 percent increase and slightly higher than the national rate.

One group in particular draws close attention: bachelor’s degree holders between 25 and 54 years-old. These mid-career workers are valuable to businesses due to their skills and experience. Out-of-state employers might recruit these workers, jeopardizing our own economic development strategies and Virginia’s goal of 70% of working-aged adults having earned a postsecondary degree or credential.

What We Know (and Don’t Know)

Measuring the mobility of different groups can be tricky. The U.S. Census conducts a basic headcount every ten years, but doesn’t give us the full picture of someone’s education and work. And because it’s only conducted once a decade, we can’t measure annual changes. The American Community Survey (ACS) fills in some gaps, with information including education attainment and whether the respondent moved from or to a different state that year. But like all surveys, ACS estimates can be blurred by sampling error and self-reporting error. It also doesn’t capture which institution, and in which state, the person earned their degree.

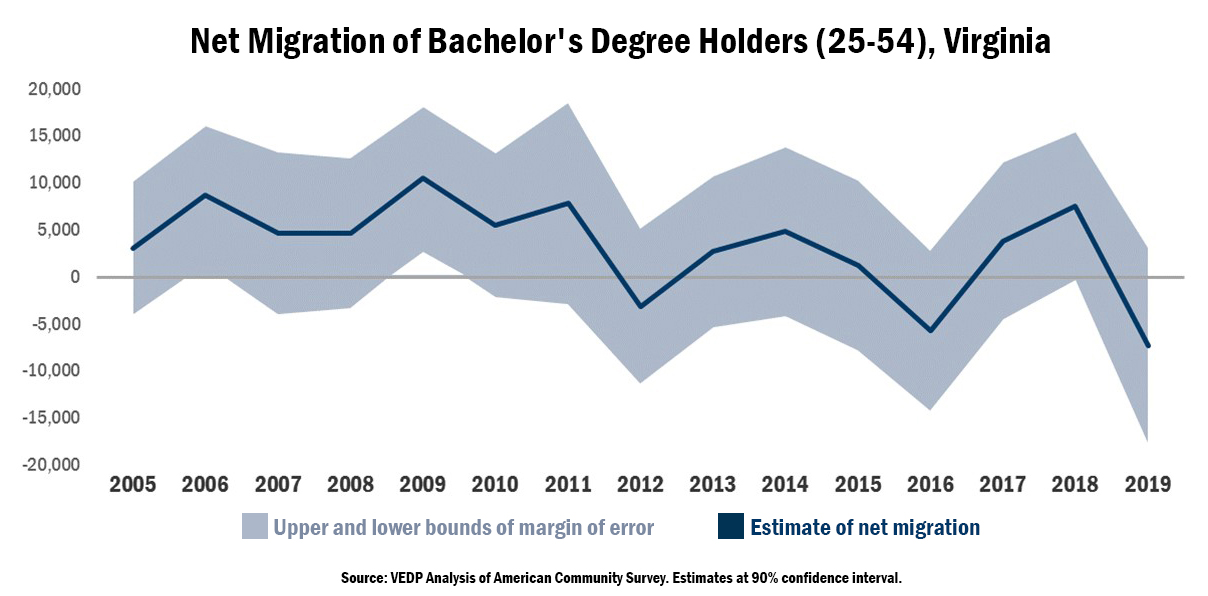

Recently our colleagues at the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP) analyzed net migration of 25-54 year-olds with a bachelor’s degree. Net migration is the difference between the number of people who moved to Virginia minus the number who moved out. VEDP found that in 2019 Virginia’s net migration for this group was -7,271. When accounting for the margin of error however, that number could be as high as + 3,063 or as low as -17,605. [1]

VEDP’s analysis was conducted at the 90% confidence interval. A higher confidence interval would produce wider variation between the upper and lower estimates.

The trends also vary from year to year. Just the previous year, in 2018, Virginia had a positive net migration of +7,535, with a margin of error producing an upper estimate of +15,430, and a lower estimate of -360. In the 15 years analyzed by VEDP, only three had negative net migration of this group. So on one hand, it’s concerning that two of those negative net migration years were in the last four years. At the same time, looking at the 15-year span, 49,000 more mid-career bachelor’s degree holders moved to Virginia than left.

North Carolina and Georgia, two states identified by VEDP as being in direct economic competition with Virginia, have seen positive net migration for this group the last three years. These estimates’ margin of error could push them to below zero, however.

VEDP’s analysis also suggests that net mobility of younger college graduates, ages 25-34 have been declining the last twenty years. The margins of error are greater, however, due to a smaller sample size.

Two other data sources at our disposal help explain the mobility of college graduates:

First, this SCHEV report matches records of students who graduated from Virginia institutions between 2008 and 2018 with their addresses provided by a third party. The advantage of this report is the user can explore mobility by institution, degree level, program or area of study, race/ethnicity, and gender. As administrative data, it doesn’t have a margin of error. The downside is that it only tracks graduates of Virginia institutions and doesn’t count graduates of colleges outside the state who moved to Virginia.

This report finds that out of 326,443 Virginians who earned a bachelor’s degree at a Virginia institution, about 9% moved out of Virginia. Of the graduates who attended Virginia institutions but previously lived in another state, 17% were still living in Virginia (there is a significant number of students whose addresses could not be found). While a greater proportion of out-of-state students stay in Virginia than in-state students leave, there are far more in-state students attending Virginia institutions than out-of-state students. This means that about 6,500 more in-state students left the state than out-of-state students stayed during this time period.

Secondly, Virginia Educated: A Post-College Outcomes Study due to be published later this year surveyed people who graduated from a public college or university in Virginia between 2007 and 2018. More than 88 percent of graduates of two-year public colleges currently reside in Virginia. Additionally, 80 percent of graduates of four-year schools who were in-state residents when they enrolled continue to live in Virginia, and 25 percent of out-of-state baccalaureate holders also have chosen Virginia as their home. Watch this space for more information about this study.

The Takeaway

In 2019, more mid-career bachelor’s degree holders moved out of Virginia than moved to Virginia. That could be an isolated event or the start of a longer-term trend. Either way, SCHEV and other agencies are paying close attention to this information and taking steps to retain the talent in Virginia.

For students, the newly created Virginia Talent + Opportunity Partnership, a collaboration between SCHEV and the Virginia Chamber Foundation, works to connect degree-seekers to an internship at a Virginia employer. The partnership hopes to encourage graduates to live and work in Virginia and provide businesses with a talented workforce. The Virginia Business Higher Education Council calls for the state to bolster its investment in internships, including a tax credit for businesses and need-based aid to help interns with expenses.

Established by the 2021 General Assembly, the Office of Education Economics will analyze policies and issues on workforce and higher education alignment, providing information and guidance to SCHEV and other partners. The office might end up providing more insight into how to retain talent in Virginia.

Making higher education equitable and affordable – two of the goals of Pathways to Opportunity, Virginia’s strategic plan for higher education – also could play a role in mobility choices. These goals help more Virginians earn a degree, develop skills and prepare for a career. Pursuing these goals also might convince more high-school graduates to enroll in college (over 25,000 high school graduates do not enroll in college 16 months after graduation) and subsequently persuade more graduates to stay.

The Virginia Educated survey also suggests that student debt plays a significant role on whether a graduate thought their education was paying off. Lowering the cost of college, and avoiding some of that debt, might allow some graduates to stay in Virginia and not leave for state with lower cost of living or higher wages.

The urgent need to extend broadband internet also plays a role. If young people – having been raised in the internet age – have no internet access, they move. As high-speed broadband access becomes available statewide, one barrier preventing some graduates from staying in Virginia will have fallen.

Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic also disrupted the relationship between where people live and work. Some workers suddenly discovered the benefits of working wherever they want, with a reliable high-speed internet connection being the only requirement. The repercussions that this flexibility in workplace location will have on mobility are still unfolding, perhaps signaling a massive and permanent shift in where people live and work.

Measuring population flows is an important, if imprecise task. SCHEV will continue to work with other state agencies, our institutions of higher education, and economic development partners to make Virginia the best state it can be.

[1] VEDP’s analysis was conducted at the 90% confidence interval. A higher confidence interval would produce wider variation between the upper and lower estimates.

Welcome to Insights, SCHEV's platform to interpret and communicate data and policy with the overall goal of informing policy-making, engaging institutions and drawing attention to these resources. Centered around SCHEV's nationally leading data collection, each Insight will visualize complex ideas and help inform funding and policy decisions.